What is Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy?

Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy is a once-and-for-all process dealing directly with what causes suffering including anxiety, depression, relationship issues and addiction. In Freud’s words “It makes its impact towards the roots, where the conflicts are which gave rise to the symptom(s)” SE Vol XVI.

At a practical level Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy involves a dynamic that is based on a double traversal. The first goes from the imaginary to the symbolic, that is the assumption of death. The second crossing is from the symbolic to the real, otherwise known as the ‘traversal of the fantasy’ – J. Lacan.

Ever wondered why psychoanalysts are called ‘shrinks’? The saying-well of wit of the analysand circles around the real cause of suffering – object a – in a spiral, “squeezing it closer and closer to the point of sculpting it” – J. A Miller. This object a, by nature meaningless, is in this analytical process progressively laid bare from its imaginary coating – the fantasy – via an operation of reduction. This bit of the real, stone, bone or as Freud would put it, ‘rock’, is ultimately at the core of what orientates the clinic.

Why do I feel so anxious?

Anxiety encompasses a spectrum of emotions and experiences, such as panic attacks, vertigo, general worry and uncertainty about life’s direction. Physical symptoms may include breathlessness, palpitations, muscle tension, fatigue, dizziness, sweating, and tremors. Unlike the ambiguity of happiness or sadness, anxiety carries a certain certainty – a palpable reality that defies words and categories.

Anxiety arises when our position in the world shifts suddenly, and our familiar self-perception undergoes a transformation. We lose reliance on the Other and can no longer use their desires as a compass for orientation. This leaves us suspended in a moment of uncertainty, unsure of our place and facing a future where rediscovery seems impossible.

Existentialist philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre views anxiety as evidence of our freedom, while Jacques Lacan explores its connection to desire. Anxiety becomes a way to sustain desire in the absence of the desired object. Conversely, desire serves as a more bearable alternative to anxiety. Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy approaches anxiety from the concept of absolute loss, a ‘lack of a lack,’ viewing desire as its remedy.

Am I depressed?

Do you notice changes in your eating or sleeping habits, whether it’s too much or too little? Are you withdrawing from people and activities due to low energy? Some may feel a sense of apathy, confusion, isolation, anger, worry, or fear, and in severe cases, even contemplate suicide. In situations where everything seems ‘perfect,’ experiencing disillusionment can be perplexing.

Depression can be seen as a force halting the natural flow of life, akin to a heart that has stopped beating. Despite outward appearances, this internal stagnation can persist unnoticed, making it challenging for some to recognize the need for investigation. Often hindered by feelings of shame, there’s a tendency to believe that we alone can change our situation.

Questions of anger, frustration, and isolation commonly intertwine with the experience of depression. In Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy, I approach this issue with the aim of reintroducing movement, using the element of surprise.

Relationship issues

Relationship breakdowns often stem from a toxic expression of aggressivity between partners. This is evident in tension, mutual rejection, jealousy, passive aggression, denial, and sometimes even verbal or physical abuse. When blame is cast upon the other, personal criticism is projected as a defensive mechanism. Referring to Hegel’s master-slave dialectic, Lacan contends that a troubled relationship is inherently ‘imaginary,’ resembling a life-and-death struggle for ‘pure prestige.’ The other is perceived as a rival, and elimination appears to be the safest resolution.

Aggressive attacks often signal a defense mechanism stuck in overdrive, with the ego under constant threat. These moments, fraught with vulnerability, lead to retaliation as a defense against the imminent anxiety of disintegration. Jealousy arises when the ego believes a competitor holds an advantage, reflecting a desire for that advantageous position and a wish to eliminate the frustrating other.

Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy addresses relational issues by unraveling the intricate threads that led to the current situation. The goal is to disrupt frozen and stereotyped perceptions and evaluations at play. Exploring significant past relationships is one avenue to understand these dynamics.

Why am I Angry?

Anger manifests in various forms, categorized as violence directed either towards others or oneself in self-harm. Outward expressions encompass bullying, threats, persecution, insults, physical aggression, power oppression, shouting, and exploiting vulnerabilities. Psychoanalysis views anger as a ‘passage à l’acte,’ an uncontrolled ‘acting out.’ Violence emerges when the Real exerts such control that the fictional self-image we’ve constructed to contain it collapses.

Paradoxically, Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy sees anger as a form of ‘deadly enjoyment,’ ultimately reflecting a rejection of perceived threats to one’s integrity. Anger, also named negative transference, may be seen as a defence against fantasies of fragmentation which the ego opposes via his desperately maintaining a somewhat coherent image of itself. For Freud hate and anger precede love in human emotions. The hostile feelings are as much an indication of an emotional tie as the affectionate ones, though with a ‘minus’ instead of a ‘plus’ sign before it. In therapy, the clinical approach involves using language to navigate and make sense of this anger (fragmented ego). Initially, the exercise of symbolization in the analytic treatment may intensify the emotion. Over time though, it should evolve into useful and creative expressions, transforming the anger into constructive productions.

Why do I feel I can’t act?

In specific situations, we might find it nearly impossible to act, instead reacting with self-consciousness and an inability to behave naturally. Symptoms of inhibition encompass reticence, procrastination, reserve, wariness, reluctance, discomfort, hesitancy, nerves, and nervousness. The experience of inhibition can be fleeting, as in a surprise accident from which we recover. If it is prolonged, it may be accompanied by feelings of isolation and anger. From an external perspective, it may appear as though nothing significant is happening. Being quiet might even be lauded as a positive trait, particularly for men. This may be so until an eventual eruption of violence severs personal ties.

Inhibited symptoms involve fear, hyper-sensitivity to others’ reactions, and feelings of disconnection or dissociation. In therapy, invoking the omnipotent presence of the Other can be beneficial. Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy emphasizes helping patients recall potentially traumatic experiences and exploring their relationships with the so-called ‘omnipotent Other.’

I Don’t feel confident

Challenges related to self-confidence and self-esteem manifest through shyness, embarrassment, unease, reserve, apprehension, and feelings of insecurity. Stemming from the experience of inhibition, issues of self-confidence can be approached in therapy by exploring the concept of power. Power can often be perceived as lacking due to a deceptive egoic image. While acknowledging the reality of low self-confidence, this ‘hole in the mirror’ can significantly impact one’s life if neglected.

Our societal expectations demand a continuous display of self-confidence, adding further pressure. Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy engages in encouraging patients to articulate their significant relationships and identify descriptions that contribute to alienation. The therapeutic goal is also to assist patients in identifying what aligns with their authentic selves, embracing their unique ‘Sinthome.’

I Have mood swings

Moods can exhibit sudden oscillations, ranging from euphoria and a sense of invulnerability (sometimes leading to uncontrollable spending habits) to morbid, self-deprecating, and even suicidal thoughts. The clinical focus initially involves establishing some stability before working towards reducing or ‘averaging’ the gaps between these emotional extremes. Explorations in therapy aim to achieve this by encouraging patients to provide detailed descriptions of their life experiences, including significant past events and the messages they absorbed while growing up.

In-depth curiosity about mood swings, their triggers, the timing of their appearance, and the factors associated with their peaks becomes a crucial aspect of Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy. Understanding the desire or willingness to explore these elements is fundamental to the therapeutic process.

Substance addictions

Addictions manifest through experiences of dependency, craving, habit, weakness, compulsion, fixation, or enslavement. From a psychoanalytical standpoint, addictions are perceived as a form of ‘self-medication,’ a strategy employed to escape everyday suffering. Intoxication not only offers immediate relief but also imparts a sense of independence from the external world. The addict can withdraw at any time, seeking refuge in a personal realm. Addiction, particularly to intoxicating substances, can drain significant physical and financial resources, potentially leaving the individual depleted or, as colloquially put, ‘wasted.’

Beyond the evident health risks, these addictions pose a looming danger of inducing enduring changes in self-perception. Statements like ‘I wouldn’t be ‘me’ without it’ or ‘I must continue achieving, and this is my crutch’ are common narratives heard in therapy. Combining substance use as a painkiller or a means to sustain a trapped lifestyle makes addiction a formidable symptom to address. While the initial challenges may seem daunting, the therapeutic power of words should not be underestimated. It is important to explore the patient’s understanding of ‘belief’ and delving into past experiences. This exercise of ‘unpacking’ which includes what was seen and heard, are pivotal aspects within Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy.

Sex issues

Impotence, obsessive sexual thoughts, porn addiction, or excessive masturbation can inevitably divert attention from establishing intimate relationships. This situation may lead the partner to conclude that they are no longer attractive. He or she may suspect about extramarital affairs, or believe the love has dissipated. In any scenario, the outcome is emotionally devastating due to the resulting lack of intimacy. Conversely, sexual activities may occur not out of genuine desire but solely to maintain an emotional bond.

In Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy, French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan asserted that ‘there is no such thing as a sexual rapport.’ As each individual has a unique path to sexual gratification, achieving complete alignment is inherently challenging. Additionally, some men may experience anxiety about being ‘swallowed up’ or the stress to perform. This may lead to some inhibition due to discomfort or closeness.

Short Biography

Upon completing a degree in Applied Mathematics at the University of Paris X (Nanterre) it was time to explore new horizons. For me at the time London offered itself as the best and most exciting option. As an Other city, London and the english language became a second home. Armed with a mathematical foundation I proceeded to study for a Bachelor of Science (B.Sc. degree) in 3D graphics with the view to building a career in film visual effects (VFX).

If working in the film industry in Soho, London, brought its fair share of rewards I could still see myself being drawn towards human sciences. So I enrolled at the Metanoia Institute, where I obtained certification in Transactional Analysis. Feeling at home in this field I then earned a diploma in Psychodynamic Psychotherapy from WPF in London. Eventually, I graduated with a Master of Science (MSc degree) in Psychotherapy from Roehampton University, London.

Today I am a fully accredited member of the British Association in Counselling and Psychotherapy (BACP) and have been practising privately in the UK since 2010. My interest is mainly working with anxiety, depression, relationship issues and addiction. My background in advanced mathematics followed by a brief excursion in computer graphics while feeling at ease working in different languages makes my clinical orientation ideally suited to Lacanian psychoanalysis.

“Stephane Preteux’s clinical skills are very advanced. His work is fully in accordance with the highest standards in the profession and bears witness to excellent reflexivity. His professional conduct with clients with a wide range of presenting problems is exemplary”

– Dany Nobus. Professor of Psychoanalytic Psychology at Brunel University London and Chair of the Freud Museum London

Fees – Budget Conscious Help

The initial assessment is £60 and is an opportunity for us to clarify the issues that have led you to consider psychotherapy, as well as your expectations as to its outcome. It may also be a chance for you to ask questions about me, my background, clinical work and qualifications as well as make your mind as to whether you feel confident that we can work together.

By the end of this session, I aim to discuss therapy options with you, including other services if for any reason therapy seems unachievable with me. If we agree to continue, we will discuss availability and fees as based on a sliding scale ranging from £60.00 for individuals who meet specific financial criteria to £75.00.

Location

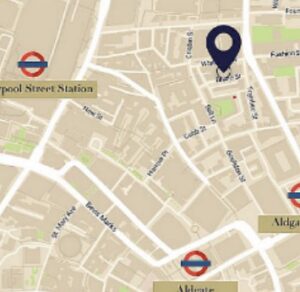

Coppergate House 10 White Row, London E1 7NF- Map here

Contact Me

To book an initial appointment you can contact me directly by phone: 07921 860498 and/or by email: stephane@lacaniananalyst.org.uk and I will get back to you within 24 hours.

Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy, Ethics and Confidentiality

In the realm of therapeutic approaches, numerous methods guide clinical practices. However, none have remained as faithfully aligned with the scientific rigor initially applied by psychoanalysis founder Sigmund Freud as the approach of French psychoanalyst Dr. Jacques Lacan. When it comes to my approach in Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy, addressing concerns like anxiety, depression, relationship issues, and addiction(s), I am primarily guided by Lacanian principles. I also believe that questions of ethics are fundamental to the analytical work itself.

If we see guilt as a direct outcome of conflicts between our deepest desires and societal demands enforcing a ‘civilized morality,’ how does the analyst navigate this terrain? It’s crucial to emphasize that psychoanalysis dismisses all ideals, including those of ‘happiness’ and ‘health.’ Instead, its role lies in encouraging patients to explore the intricate relationship between their actions and desires. In Freud’s words, “The analyst respects the patient’s individuality and does not seek to remold him in accordance with his own personal ideas; he is glad to avoid giving advice and instead to arouse the patient’s power of initiative“.

Confidentiality in therapy holds utmost importance and can be a significant concern for many clients. In my practice, the management of confidential materials between sessions adheres strictly to the Ethical Framework for Good Practice in Counselling & Psychotherapy outlined by the BACP (British Association for Counselling & Psychotherapy). The following list encapsulates the issues related to confidentiality, and for my practice, it is a matter of:

- Autonomy, which entails respecting the client’s right to self-governance, is a crucial aspect. Practitioners upholding autonomy take measures to safeguard privacy and confidentiality. They typically condition any disclosure of confidential information on the consent of the person involved. Additionally, practitioners inform clients in advance of foreseeable conflicts of interest or as soon as such conflicts become apparent..

- Providing a good standard of practice and care: All clients are entitled to good standards of practice and care from their practitioners in counselling and psychotherapy. Good standards of practice and care require professional competence; good relationships with clients and colleagues; and commitment to being ethically mindful through observance of professional ethics.

- Respecting Privacy and Confidentiality. Respecting clients’ privacy and confidentiality is crucial for building trust and upholding client autonomy. The professional management of confidentiality involves safeguarding personally identifiable and sensitive information to prevent unauthorized disclosure. This protection can occur through authorized disclosure based on client consent or legal requirements. Disclosures, when necessary, should prioritize maintaining the client’s trust and respecting their autonomy.

- Client Consent and Ethical Considerations Communications made with client consent do not breach confidentiality. Client consent is the preferred ethical approach for addressing confidentiality dilemmas. However, exceptional circumstances may arise, such as situations requiring urgent action to prevent serious harm to the client or others. In these cases, practitioners must ethically balance confidentiality against the need to communicate. Practitioners are accountable for any breach of confidentiality and should maintain good records of policy, practice, and situations where breaches occurred without client consent.

- Sharing Confidential Information and Legal Constraints Confidential information may be shared within teams with client consent or when the client knowingly accepts a service on this basis. This sharing should enhance the quality of service or improve service delivery while ensuring information security. Practitioners must be willing to be accountable to clients and their profession for confidentiality management. Legal constraints may prohibit practitioners from informing clients about passing confidential information to authorities in specific situations. Despite legal limitations, ethical accountability to colleagues and the profession remains.

Frequently Asked Questions

If help is available to deal with anxiety, depression, relationship issues and addiction it may not remain an easy process to go about deciding to find the right person to talk to. Below is a list of the most frequently asked questions around starting psychotherapy ‘on the right foot’.

What is psychotherapy?

Psychotherapy is an opportunity for you to talk safely in a confidential place about your life and all that may be confusing, painful or uncomfortable. The therapist is someone who is academically trained to listen attentively so as to help you cope better.

How therapy will make me feel?

Therapy is a process which is personal. Going through painful experiences may feel as if things are worse than when you started. In the long-run however therapy should help you feeling better. If it doesn’t after a while you should let your therapist know that things are not improving.

Will I feel better straight away?

Apart from rare occasions where a single session is enough it usually takes a number of sessions before therapy starts to make a difference.

Does it work for everybody?

No. Because everyone is different (therapist included) everyone will feel the therapeutic process differently. Some therapy are successful, others are less. The relationship with the therapist is central to any progress.

Will I be able to have therapy that understands my cultural background?

It is important that you find a therapist you find yourself comfortable with, which could mean that you want to search for someone who is aware of your cultural background. Having said this it should not matter for the therapist.

Are therapy all the same?

No. There exists different methods and approaches in therapy and you might want to discuss the various modalities with your therapist so as to be sure his or her way of working will be all right with you.

What types of therapy are there?

Many different types of therapy are available. However it is often found that your relationship with the therapist is central to the progress of therapy.

How long does therapy take?

Sometimes only one session is enough to feel better. However, as the therapy progress it may be the case that sessions continue over several weeks or months. It is common practice after 6 or 12 sessions to review how therapy is going for you, and discuss whether you feel it is important for you to continue or not.

How long is a session?

Sessions usually last fifty minutes to one hour. However it is also the case that some modalities extend or shorten this time

How often will I see my therapist?

Usually people see their therapist once a week. However this frequency can change if you wish a more intense therapy dealing with anxiety, depression, relationship issues and addiction. This should be made clear from the start in the initial session with your therapist.

What questions should I ask the therapist before therapy begins?

The following are a list of recommended questions, however do also ask your therapist any others that you think of: – How many sessions will I have? – What type of therapy do you offer? – How much will it cost? – What happens if I miss a session? – What happens if I want to take a holiday, will I still have to pay? – Will the counselling be confidential? – Will you make notes during the session, and if so, what happens to these? – Can I contact my therapist in between sessions?

What should I look for in a therapist?

The initial assessment is a chance for you to ask about the qualifications the therapist has and whether he or she is a member of a professional body such as: – The British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy – The United Kingdom Council for Psychotherapy – The British Psychological Society You might also want to check whether the therapist has any experience and/or training in any particular area of concern important to you.

How can I be sure this particular therapist is right for me?

Trust your first impressions. If might just be that after a few minutes you feel you can trust the therapist and that you are comfortable talking about your issues with anxiety, depression, relationship issues or addiction. If on the other hand you feel not quite at ease, you may want to reconsider your choice of therapist.

What if I don’t like my therapist?

If after several sessions you don’t like your therapist you may want to address the matter with him or her. This might just be part of the therapeutic process iself (transference). If after a while there is still a real and long lasting discomfort then you may wish to consider seeking another therapist.

What can I do if it doesn’t seem to be working?

If you feel that after a while there doesn’t seem to be any difference for you, it is important that you discuss this with your therapist. If then nothing changes then you may wish to go to another therapist.

How do I know if my therapist is qualified?

400-450 hours college-based therapy training is the number of hours BACP recommends as a minimum. You may want to ask your therapist for the details of their qualifications. Don’t hesitate to ask questions. If you still feel unsure, do contact the therapist’s professional body in order to verify their qualifications.

Does a therapist have to be licensed?

Currently there is no legal requirement for therapists to be licensed to work with anxiety, depression, relationship issues and addiction. However, it is wise to choose a therapist who is a member of a professional body and who is insured to practice.

I want to end therapy. How can I do it?

If after a while you would like to end therapy it is preferable that you first discuss it with your therapist in order to bring things to a clean end. If this seems too difficult to do face to face, you may want to give notice of wishing to end therapy in writing. Please do bear in mind any agreement you made at the beginning of therapy with regards to ending sessions.

Will I be charged if I cannot attend a session?

It is important that you discuss this when you make your agreement with your therapist at the start of therapy. Because the rooms I am using require me to be charged on an ongoing basis unless in exceptional circumstances I am charging for missed sessions.

What if I am on holiday and so will miss a session?

It is important that you discuss this when you make your agreement with your therapist at the start of therapy. Because the rooms I am using require me to be charged on an ongoing basis unless in exceptional circumstances I am charging for missed sessions.

Will what I say in therapy be reported outside the room?

What is being shared in therapy is confidential to the extent that it will not be reported to anyone except a supervisor who, for the protection of the client also offers his or her own interpretations and make sure no harm is being done. In other circumstances however, if there appears to be a serious risk of harm to you or to others the therapist should inform you of his or her intention in dealing with this situation. This is usually done with your permission. These circumstances should be explained to you at the beginning of your therapy.

How much will I have to share with my therapist?

While at work on dealing with anxiety, depression, relationship issues and addiction what you tell your therapist is entirely up to you.

Will the therapist contact my doctor?

Therapists usually ask to have your doctor’s contact details in case they feel there is a serious risk of harm to you.

Is it possible to bring a friend?

This is not encouraged. The therapy is for you and is safe because what you talk about is explored in depth between you and your therapist. If there are communication difficulties, it would of course be understandable to have an interpreter in the room. If you feel you would rather be with other people in therapy you may consider group therapy.

Useful Links dealing with anxiety, depression, relationship issues and addiction

Professional Organizations dealing with anxiety, depression, relationship issues and addiction

- UKCP – United Kingdom Council for Psychotherapy – ukcp.org.uk – Tel. 020 7014 99 55

- BACP – British Association of Counselling & Psychotherapy – bacp.co.uk – Tel. 01455 883 300

- BPS – British Psychological Society – bps.org.uk – Tel. 0116 254 956

Other Useful Websites dealing with anxiety, depression, relationship issues and addiction

- Department of Health – dh.gov.uk – Tel. 0845 4647

- Mental Health Care – mentalhealthcare.org.uk – Tel. 0845 4647

- Mind – National Association for Mental Health – mind.org.uk – Tel. 0845 766 0163

Psychotherapy Training Organizations and Services dealing with anxiety, depression, relationship issues and addiction

- Institute of Family Therapy – instituteoffamilytherapy.org.uk – Tel. 0207 391 9150

- Institute of Psychoanalysis – psychoanalysis.org.uk – Tel. 0207 563 5002

- Guild of Psychotherapists – guildofpsychotherapists.org.uk – Tel. 0207 401 3370